It may sound like science fiction, but soon, some of Sweden's biggest emitters may be able to capture and store some of the carbon dioxide they emit. The technology exists and we have tested that it works. Right now, we are working to have a first carbon capture facility operational by 2026.

Can a large sandstone reservoir 3000 meters below the seabed 11 miles off the coast of Norway be part of the solution to the climate challenge? The technology – carbon capture and storage, or CCS - has been in operation in Norway since 1996.

The Norwegian energy company Equinor has 23 years of experience storing carbon dioxide and can now see a new market opening up. In December, they will start drilling the hole to confirm that the conditions for storing carbon dioxide are as good as expected.

Per Sandberg works with new energy systems at Equinor. He has a wealth of experience since the 1990s, both as a researcher and in the business world, and knows all about CCS technology.

How does carbon capture work?

– First, let me say that this is not a new technology. It has been around for 20-30 years already. The main challenge is that it is still very costly – not that the technology is too complicated. To put it simply, there are two different ways to collect carbon dioxide that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere, says Per Sandberg.

– One way is to capture carbon dioxide from flue gasses generated by combustion or an industrial process. The other technique is called pre-combustion. In hydrogen or fossil gas treatment, you split the gas in two to get one stream with carbon dioxide and one with hydrogen. This captures the carbon dioxide before combustion. Preem will be utilizing the first technology at its test facility, which will be in operation in early 2020.

What happens to the captured carbon dioxide?

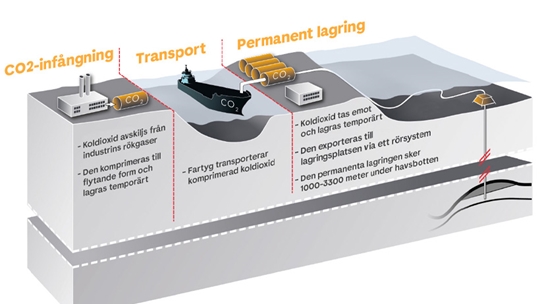

- It will be purified and concentrated; in Preem's case, the plan is to liquefy it. Our ships then collect the carbon dioxide every four days to transport it to an intermediate storage site near Bergen. It is then piped down to Equinor's storage site far below the seabed. All this is expected to be in use for partners outside Norway by 2024 or 2025.

How does the storage work?

– We have found an area south of Troll, a well-known oil and gas field, where we do not believe there is oil. At a depth of 300 meters, we will drill a 3000-meter-deep hole in the seabed. At that depth, we have identified two important features for the storage. It is an area of sandstone which is more porous than other bedrock. On top of the sandstone is a roof of impermeable rock, says Per Sandberg.

– The pores in the sandstone are filled with water, so when we start injecting carbon dioxide into the sandstone, it displaces the water and replaces it with carbon dioxide. Initially, we hope to store 1.5 million tons of carbon dioxide here each year.

The major obstacle to realizing the technology is about something other than limitations in storage capacity. There are currently no financial incentives, although more and more people are starting to take notice of the technology, says Per Sandberg.

– The storage capacity under the North Sea as such is enormous. It corresponds to several hundred years of Europe's carbon dioxide emissions. The major limitation is that it is still cheaper to emit carbon dioxide than to capture it, he says.